So this’ll be another article about neural networks on the Internet. So why another one? I think most of the articles are either too shallow or too technical. This won’t be comprehensive but it’ll give you the basic intuition to understand how neural networks work at the very high level.

The purpose of a neural network is to solve a problem, just like any other computer program. So we need a problem to use it as an example. We can use a very popular and interesting challenge: numerical digit recognition.

Also,

to make it simpler we’re only trying to find out if the digit in the image is

one in particular, the 6. If we solve the problem for this digit we just

have to repeat the same for all other digits.

To get started, we need to be able to define the problem we’re trying to solve in mathematical terms. We want to define a function:

\[f(x) = y\]Where \(x\) is the input image, \(y\) is the probability of the image to

contain a 6 and \(f\) is the function we need to solve.

The input image \(x\)

So the first thing you may be wondering is how can \(x\) be an image and how can we operate with it mathematically? Well, we can represent our image as a matrix or a even a vector.

Let’s make some conditions for our input image:

- Size is \(24\times24\) pixels.

- Only colors are black and white.

- White pixels are represented with 0.

- Black pixels are represented with 1.

That image format is good enough to allow digit recognition, at least for a human being. See some examples:

Then our image can be represented as a matrix of \(24\times24\) numbers. For example, we can have a white image \(A\) and a black image \(B\) as follows:

\[A,B\in\mathcal{M}_{24\times24} \\ A = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix}, B = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]However, to make it simpler we’ll represent it in a row vector of \(24\times24 = 576\) numbers instead. Now, our white image looks like this:

\[A'\in\mathcal{M}_{576} \\ A' = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \end{bmatrix}\]The \(f\) function

Our function will be as simple as:

\[f(x) = x \cdot W\]We just need to find a vector \(W\) so that:

\[x \cdot W = y\]For example, if \(I\) is an image containing a 6:

Training

The challenge now is to find values for \(W\) so that:

\[\text{For any image $x$ that contains a 6:}\\ x \cdot \begin{bmatrix} w_1 \\ w_2 \\ w_3 \\ \cdots \\ w_{576} \end{bmatrix} = 1\] \[\text{And for any image $x$ that doesn't contain a 6:}\\ x \cdot \begin{bmatrix} w_1 \\ w_2 \\ w_3 \\ \cdots \\ w_{576} \end{bmatrix} = 0\]Spoiler alert, we’ll never find the perfect fit.

But we’ll get as close as possible.

The values in \(W\) are often called weights or training parameters. We’ll iterate many times, making small adjustments and getting closer. For that, we need:

- A way of measuring how close we’ve got.

- An algorithm to determine what small adjustments should be applied.

To measure how close we’ve got we need a training dataset, that is a large

collection of images on which we know for each one if they have a 6 or not.

Once we have a training dataset we can define a loss function which sort of indicates how big is the gap between the perfect \(W\) and our current one. It does this by comparing the values of our current predictions with the actual ground truth from our training dataset.

The goal is to reduce the loss as much as possible. If it reaches zero it means we’ve found the perfect \(W\), but this very rarely happens.

With a loss function we can use an algorithm such as gradient descent to gradually adjust \(W\) towards our goal. I won’t go into detail about the maths that make gradient descent work, but I’ll just say that it’s a computationally very expensive process which will iterate until we settle for certain accuracy/loss/limit/etc. This process is called training, and it’s preferably ran on a GPU or even a TPU.

Predictions

When training is completed we’ll have our weights and should be able to infer

if an image contains a 6 or not. An example might look something like this:

That’d mean that the model is \(94.23\%\) confident that the image contains a

6.

Personally, I find it fascinating that our function now is able to predict numbers that are not part of the training dataset. It could be said that it has learned what a six is.

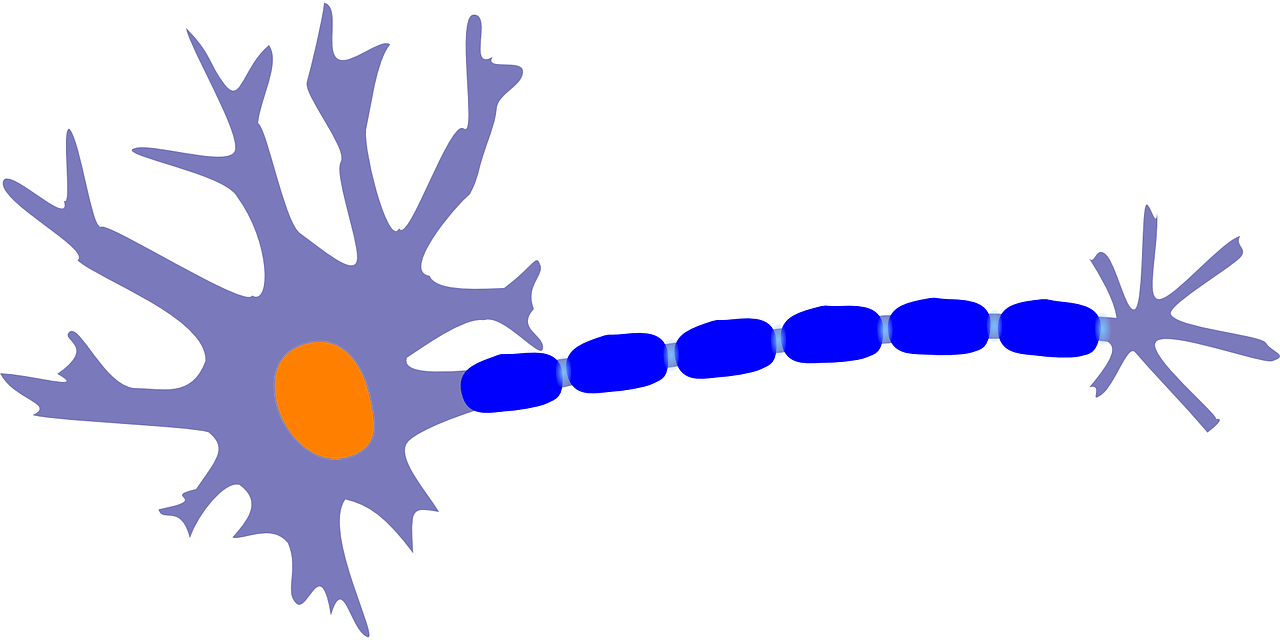

Where are the neurons?

What we’ve seen in this article would be a very basic neural network model with a single fully connected layer of neurons. More specifically, we had one single neuron with 576 inputs. This neuron was able to detect a particular digit, we could add 9 more neurons to detect all the other digits. So we’d have 10 neurons and 10 outputs.

Most useful neural networks use more complex architectures where the output of the first layer is the input of a second layer, and maybe a third one and so on. This way of stacking layers of neurons is used by deep neural networks or DNNs.

Other models are able to detect patterns and features in images using convolution. These are called convolutional neural networks, and have a very different layout.

But all of them have the same concepts as our basic model:

- Have a set of weights that need to be optimized.

- Use an algorithm similar to gradient descent to find those weights.

- After training, we use the learned weights to do the predictions.

This mathematical model is inspired by the way neurons work, where the electric pulse generated by one neuron is fed into the next neuron in a giant mesh. But electric pulses are represented by numerical values here.

Keep on going!

Bear in mind that I’ve omitted a good bunch of details to get to the point as quick as possible (and still the result is quite long!). All I wanted is to explain very roughly what’s inside neural networks.

If you found this topic interesting and want to dig deeper you’re encouraged to try Tensorflow, this tutorial will guide you through the implementation of an algorithm to solve digit recognition.